Winners of the income shift: how Asia is reshaping global markets

Over the past forty years, the map of the global economy has been fundamentally redrawn. While growth in developed countries is slowing, emerging Asia – led by China and India – is redefining what it means to be part of the “middle class” today. The shift in the income pyramid is not just a statistical curiosity, but also the most profound structural process in the global economy: new consumer groups are already influencing corporate strategy, capital flows, and investor thinking.

The new map of the global middle class

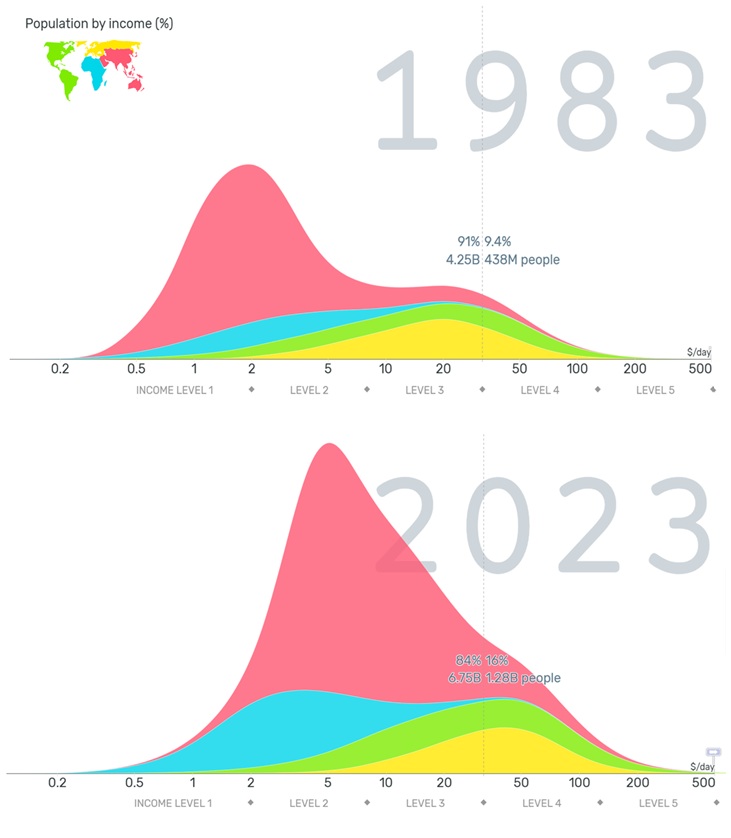

In 1983, only a fraction of the world’s population earned more than $32 a day (i.e., $960 a month, or 315,000 forints at today’s exchange rate), which is considered by the World Bank to be the lower limit of developed consumer levels. Since then, the ratio has tripled, and the middle class no longer lives exclusively in London, New York, or Paris, but also in Seoul, Singapore, Shanghai, and an increasing number of South Asian cities. However, the process is far from over. It is estimated that by 2027, half of the world’s consumers will no longer come from traditional Western countries, and by 2040, this proportion could reach 60 percent. The economic trends of the next decade will be determined not by the demographics of the developed world, but by the consumption habits of the middle classes in emerging regions.

Source: Gapminder

China and India: the two faces of growth

China is the most striking example of this process. Today, more than 120 million people in the country earn over $960 a month and are becoming increasingly conscious consumers. The emphasis is shifting from quantity to quality, technological developments, health, and leisure. The new demand patterns emerging in the country extend far beyond its borders: luxury brands, electric car manufacturers, and digital service providers are all looking to China for their next source of growth. India is on a different path, but the prospects are similarly promising. The world’s most populous country is still in the early stages of its growth story: today, just over one percent of the population has an income above the threshold mentioned above. However, its young and educated population, urbanization, and digitalization hold enormous internal potential. Income growth, investment, and consumption could trigger a self-reinforcing cycle that could make India Asia’s second engine in the long term.

Central Europe on the path to convergence

Income redistribution has not bypassed Central Europe but striking differences have emerged within the region. In Hungary, 36 percent of the population belongs to the income category exceeding the “Western consumer” threshold, while in the Czech Republic and Poland this proportion is close to 55 percent. In Slovakia, on the other hand, it is only 14 percent, while Austria, with 86 percent, is part of the developed European core. Although the region has caught up significantly over the past two decades, wage convergence is not yet complete. The key question for the coming years will be whether Central Europe – especially Hungary – will be able to move away from labour-intensive sectors toward higher value-added industries. Growth will only be sustainable if the region’s economy not only creates more jobs, but also increases productivity, strengthens innovation capacity, and enhances technological integration.

The new economic balance of emerging markets

The current structure of capital markets does not yet reflect the economic reality of the world. The MSCI ACWI equity index, which covers 85% of global investable equities (representing 23 developed and 24 emerging markets with large and medium market capitalization companies) North America dominates, but only 30% of the revenues of the companies included in the index come from this region. Emerging markets, on the other hand, represent only 12% of global market capitalization, yet account for 42% of global corporate revenues. This imbalance shows that capital markets are undervaluing developing economies. According to IMF forecasts, these countries will continue to grow two to three percentage points faster than the developed world in the coming years, meaning that a significant proportion of global growth could come from here.

The geographical exposure of global companies

Economic restructuring is also evident at the sectoral level. The world’s leading stock market indices, such as the US S&P 500 and the European Stoxx 600, increasingly include companies that generate a significant portion of their revenues abroad. The technology, industrial, pharmaceutical, and consumer sectors are now almost completely globalized: their growth is determined not by the economic cycle of a single country, but by global demand and the international reach of supply chains. In contrast, utilities, sectors linked to local infrastructure, and services that rely on domestic markets remain strongly domestic-focused and are therefore more sensitive to the national regulatory environment and economic policy changes.

However, there are marked differences between developed and developing economies. In emerging countries, the vast majority of companies still rely primarily on domestic demand, so the share of domestic revenues is higher in all sectors. This suggests that these companies are less competitive in international markets for the time being, but it is precisely this limited international presence that holds the greatest growth potential. Through foreign market entry, technology transfer, and capital flows, these companies could gradually integrate into the global economy over the next decade.

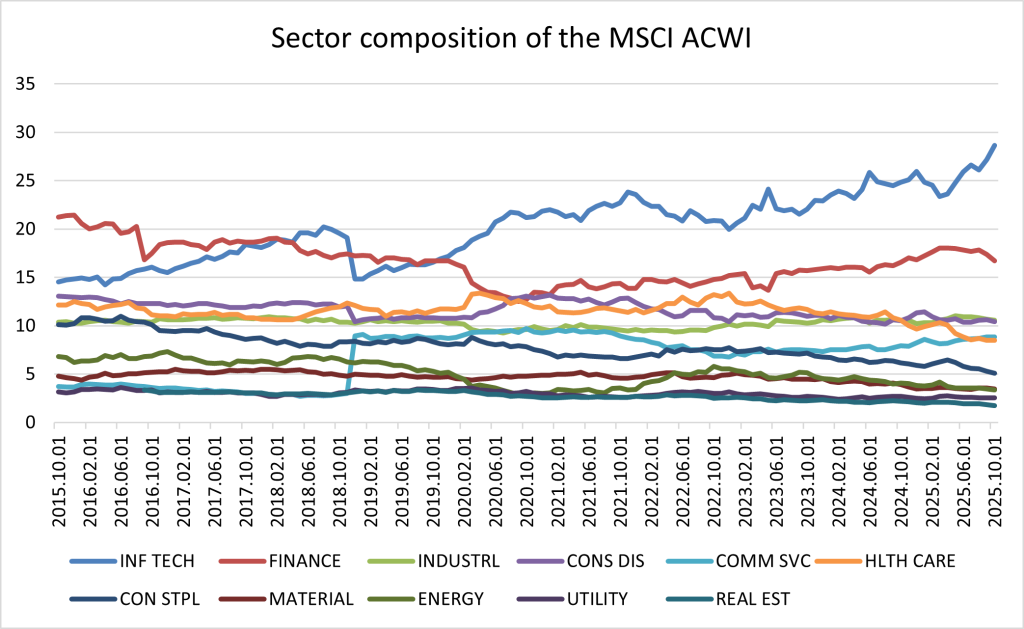

Source: Bloomberg

At the same time, the sectoral structure of international stock indices is gradually shifting towards sectors with greater international exposure. The technology and consumer goods and services segments have gained increasing weight in the indices in recent years, reflecting not only changing investor preferences, but also the fact that these sectors offer the greatest long-term growth potential. International presence and revenue diversification are thus increasingly becoming the keys to market success in global corporate valuations.

The international revenue structure has become crucial in corporate valuations: the more diversified the market, the more resilient the company is to regional economic fluctuations. This phenomenon is already clearly visible on the American and European stock exchanges, where the share prices of the largest players are increasingly driven by demand from Asia and Latin America.

A new era of growth – a new balance

At the same time, the map of global demand is being completely redrawn. The engines of economic growth are revving fastest in Asia, Latin America, and Africa, where rising incomes are giving rise to new consumer behaviours. For international companies, this marks the beginning of a new era: global brands are no longer conquering markets with uniform products and messages, but with increasingly sophisticated, localized strategies. The key to success has become cultural sensitivity, knowledge of local income conditions, and flexible adaptation to consumer preferences. Where income grows, so does demand – and this is reflected in corporate profits, stock market valuations, and ultimately in global growth prospects.

Emerging economies will continue to be the main drivers of global economic growth in the coming decade. Measured in terms of GDP, they are expected to grow two to three percentage points faster than the developed world each year, and this catch-up process will become one of the most important structural trends in the global economy. However, it is not only local companies that will reap the benefits of this growth. Innovative international companies that are able to adapt to the needs of the emerging middle class will continue to capture a significant share of this dynamic market.

Even if the pace of globalization slows, economic ties will not disappear – they will simply transform. New networks of capital, technology, and consumption patterns will emerge, in which regions will not separate but connect in new ways. Future growth will thus be a story not of the separation of the world’s regions, but of the emergence of a new equilibrium: a multipolar, interconnected world where the engines of growth no longer come from one direction, but from all directions at once.

Legal Notice: The operator of this blog is VIG Asset Management Hungary and the authors are employees of the Asset Management Company. This website contains commercial communication. The articles published on the blog reflect the subjective opinions of private individuals, are prepared for informational purposes only, and do not constitute investment analysis or investment advice, nor do they contain any investment recommendations. The authors of the blog may trade in their own name in financial instruments, funds, or other products about which they provide information or express an opinion in their articles. While the authors’ experience gained in stock exchange or over-the-counter trading may be reflected in their writings on this blog, such interests must not influence the information they provide. Articles, news, and information on the blog may feature companies that maintain business relations with VIG Asset Management Hungary or with the authors of the blog, either directly or through another company belonging to the VIG Group. The articles published on this blog do not provide complete information and do not replace the assessment of the suitability of an investment, which can only be determined by evaluating the individual circumstances of the given investor. To make a well-founded investment decision, please seek detailed information from multiple sources.

VIG Asset Management Hungary, the editors, and the authors of the blog accept no responsibility for the timeliness, possible omissions, or inaccuracies of the content on the blog, nor for any investment decisions made on the basis of the blog articles, or for any direct or indirect damage or cost arising from such investment decisions.